Finding Reasons to Work Hard vs Finding Excuses to Do Less

Even the best heuristics aren't perfect - but they are incredibly useful

One of the most important parts of my growth and evolution as a strength coach was learning, roundabout 15 years ago, that no matter what the long term fitness goal, getting strong first is almost always the best way to start. You can find a very rare exception, and certainly we aren’t trying to turn triathletes into powerlifters, but for the regular person just trying to improve fitness, and even many athletes who haven’t done proper strength training before, getting strong first will help more than anything else.

In that respect, “Get stronger first, no matter what” is an example of a heuristic - and an excellent one at that. It’s a shortcut, a practical piece of advice that may not be 100% optimal in every possible circumstance, but is perfectly sufficient as a simple and reasonable solution to a complex question (“What should I do to get fitter?” or similar) that will avoid paralysis by analysis, cognitive overload, and putting lots of effort into stupid things.

Another example of a heuristic that we coaches use a lot is telling our lifters to buck up and just do it. Stop making excuses. I know it feels heavy - it’s supposed to. I know your kid woke you up 3x in the middle of the night - that’s life. I know you didn’t eat your last meal at the perfectly peer-reviewed optimal time to deliver intra-workout energy and promote post-workout muscle protein synthesis - but that’s life. Do you want to get weaker or stronger? Suck it up and do it anyway.

This is such a good heuristic because the overwhelming majority of people try to find excuses to do less, rather than reasons to do more. I don’t know the actual numbers but based on my experience of almost 2 decades doing this for a living, when it comes to fitness endeavors, I’d guess about 95% of people will make excuses to do less, about about 5% will try to find reasons to do more. The story I told in my “The Elusive RPE 6” post about the guy who wanted to squat 405 even after barely making 385 is an example of that - but they’re very rare.

However, they’re not so rare as to be essentially absent, and as coaches, we need to be on the lookout for this rare but not impossible scenario because it does happen. Much to my chagrin, I lost a couple clients 6-7 years ago to a rival who I, shall we say have less than warm & fuzzies about, because I used the regular heuristic instead of spotting that they were exceptions. The disappointment in myself that I didn’t serve them as well as I should have, as well as driving them into the arms of people I don’t particularly love, created a dual incentive for me to be more careful about applying even excellent heuristics carelessly.

That said, the situation is different when giving general advice to the public than it is coaching a specific lifter. In the latter case, you get to know the person, their mindset and attitude and quirks. You can spot if they’re an exception, if you pay close enough attention. In the former case, unless you want to make your every statement so full of caveats and CYAs so as to be meaningless, it makes a lot more sense to just give really good general advice, and let the few exceptions figure things out.

What’s the upshot of all this? Well, I came across the following exchange today in a lifting group I’m in, and it provides an excellent example of this very issue in action. Because the group is private, identifying information has been removed.

The initial question:

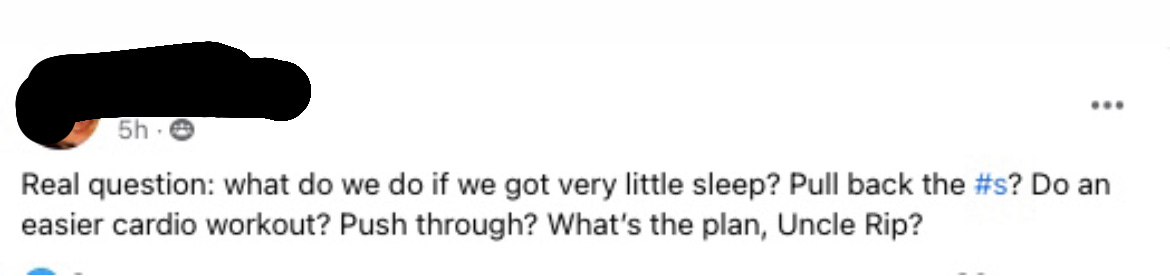

The first reply:

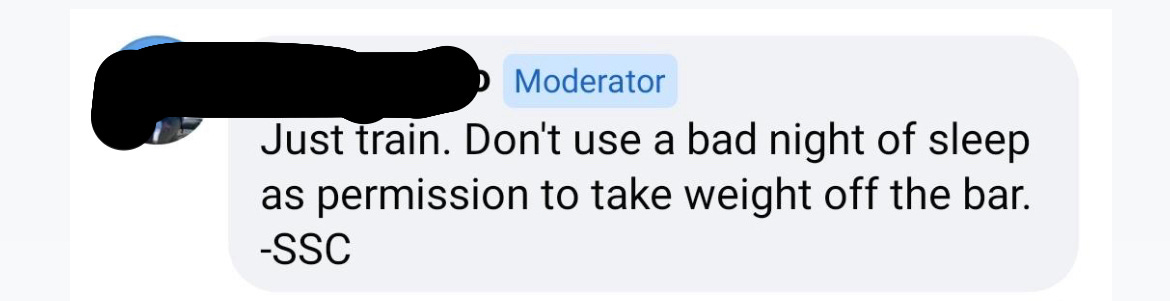

The next reply:

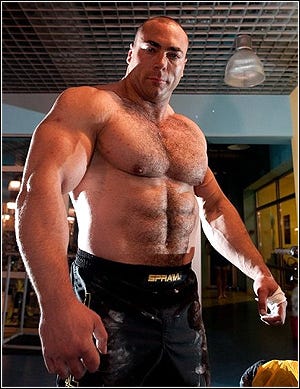

Which reply is better? I’ll let you think about that for a minute, keeping in mind what I’ve written above. To keep you company while you contemplate, here’s a picture of the late great Konstantin Konstantinovs, who deadlited almost 950 lbs but was tragically murdered about 5 years ago in his capacity as a bodyguard (as best we know, it’s a bit of a mystery still).

The first reply is applying the 95% heuristic. Understanding that the vast overwhelming majority of people look for excuses to do less, not reasons to do more, and in the absence of specific information that you know otherwise, it makes sense to give the 95% advice.

The second reply has lots of nuance and understanding and we might even say compassion and empathy. It validates the struggle with being tired, it tells you that’s just part of the game and does this ONE workout really matter that much anyway? It provides the ready made excuse to do less, which the lifter will be happy to hear, and then do less.

This is an interesting issue because there are people for whom the 2nd answer is better - just not very many of them. I say 95%, but that’s really just me pulling numbers out of my butt. I don’t know if it’s 93%, 95%, or 99%, but it’s definitely a rare exception. So unless I know for sure that’s the type of person I’m dealing with, it makes much more sense to say: Suck it up and just do it. Do the hard work. Embrace it, welcome it, and overcome it. That’s your only job for your hour or hour and a half in the gym. JUST DO IT.

I’ve had more workouts than I can count or remember where I felt like absolute donkey manure heading in, where warmups felt like they weighed a ton, and then I managed to do all my planned work without a problem - sometimes even set a PR. And I tend to be more of someone who finds a reason to do more, and this is STILL the case! If you include my clients, the number is well into the hundreds. Usually if you get to work and just do it, you’ll succeed and be fine.

But what if you’re wrong and the person or situation was an exception? Well, they’ll quickly learn. And this is by definition going to be a relatively inexperienced lifter, for whom failing a weight won’t cause any kind of massive systemic stress the way grinding against 700 for 8 seconds before failing would. No one who’s gotten to 700 doesn’t already know how to handle a lack of sleep. It’s definitionally going to be a beginner or early intermediate who doesn’t yet know what to do here.

By giving her an excuse to do less, the coach is letting over-empathization and excessive nuance feed into exactly the answer most people want to hear. The excuse they were looking for anyway. Which is why, even though the answer isn’t categorically wrong the way 2+2=5 is categorically wrong, it’s still bad advice.

Find a reason to work harder. Not an excuse to do less. Not just in the gym, but in life.