The Amazing Hipparchus

More than two thousand years ago, a Greek astronomer called Hipparchus calculated the length of a year to within 0.005 days of the current figure. And he didn't even have a telescope.1 2

Hipparchus was born in 190 BC in Bithynia, a region in the north-west of modern day Turkey. Much of what we know about his life is speculative: he probably died in Rhodes and may have travelled to Alexandria. What survives of his work comes down to us from other writers.

But we do know that Hipparchus was a genius. He is the father of trigonometry, created comprehensive star charts, calculated (to varying degrees of accuracy) the size of and distance between the earth, moon, and sun, and advanced the study of geography.

One of Hipparchus' greatest achievements was (we think) helping to design the Antikythera Mechanism, a complex astronomical device used to predict the dates of eclipses and other celestial events.

And it was to astronomy that Hipparchus made his most famous contributions. Before him came many great Greek astronomers such as Eratosthenes, who accurately calculated the circumference of the earth, or Aristarchus, who theorized that the earth revolved around the sun.

But Hipparchus is regarded as the greatest of them all. There are many reasons for this, and his calculation of the length of the year is just one of them.

How did he do it?

Some had tried before. Callippus, for example, said in 330 BC that a year was 365 1/4 days long. Hipparchus wanted to know if this was correct. And so, perhaps using astronomical devices he invented, Hipparchus calculated the length of the year himself. He did so, like his predecessors, by measuring how long it took for the sun to return to the same position in the sky.

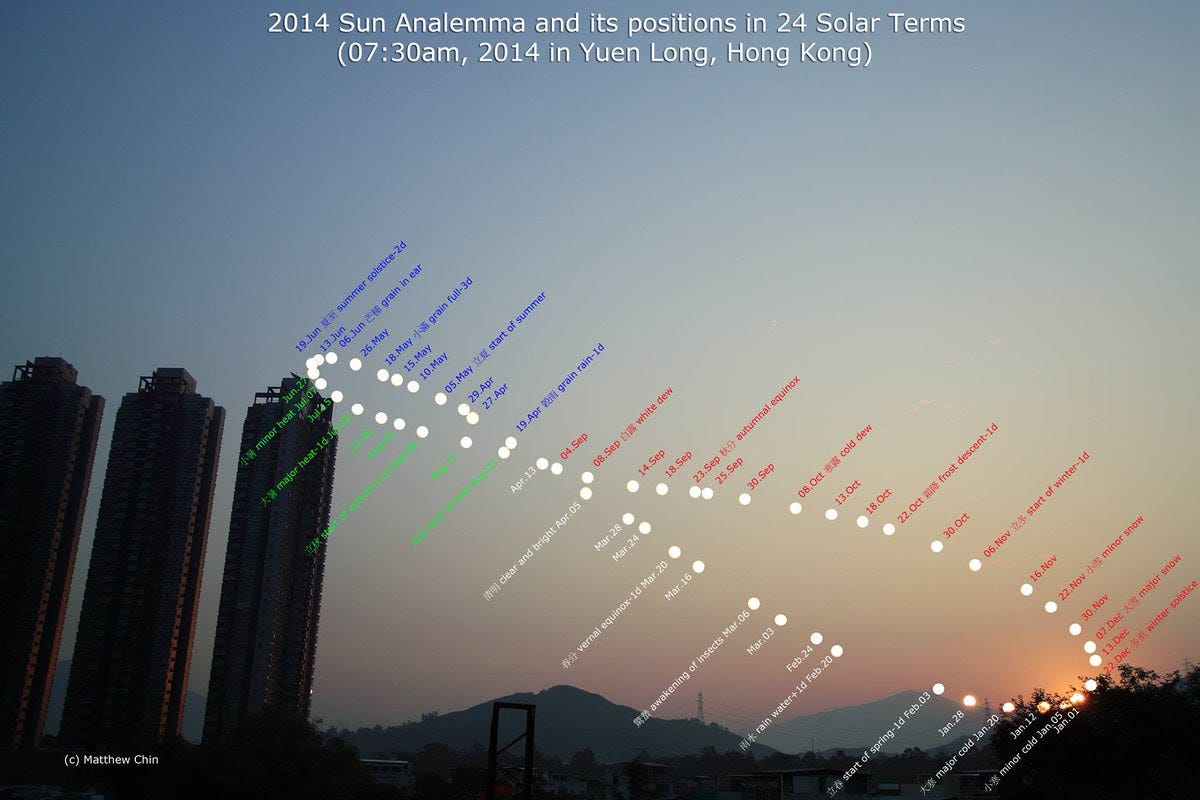

The sun changes position throughout the year. If you take a photo of the sun at the same time each day from the same location, over the course of a year it creates a shape known as an "analemma". When it hits the exact same spot again, a year has passed.

Hipparchus' results were inconclusive and varying - he simply didn't have enough data. So he consulted the detailed astronomical records of his fellow Greeks and, crucially, of the Egyptians and Babylonians; they had been keeping records for centuries.

And when he looked at the ancient records he found discrepancies. Specifically, Hipparchus figured out that over the course of about three hundred years, there had been a shift of almost precisely one day in the timings of recorded celestial events (such as the solstice).

And so he reasoned that Callippus' calculation was wrong by 1/300 of a day. Hipparchus subtracted 1/300 from 365 1/4 and arrived at 365 74/300 as the length of a year. Or, in decimals, 365.2467.

In over two millennia since, we have improved on that figure by only 0.0045, as the year currently is calculated as 365.2422 days.

Hipparchus’ legacy lives on thousands of years after his time: The lunar crater Hipparchus and the asteroid 4000 Hipparchus are named after him. He was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 2004. Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre, historian of astronomy, mathematical astronomer, and director of the Paris Observatory, considered Hipparchus along with Johannes Kepler and James Bradley, the greatest astronomers of all time. The Astronomers Monument at the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, California, United States features a relief of Hipparchus as one of six of the greatest astronomers of all time and the only one from Antiquity.

The Problem

Hipparchus was a pioneer of astronomical instruments, but he and his fellow astronomers had far fewer technologies than we do in the 21st century. It was with their eyes and minds - unaided by telescopes, computers, or satellites - that they came to understand the universe.

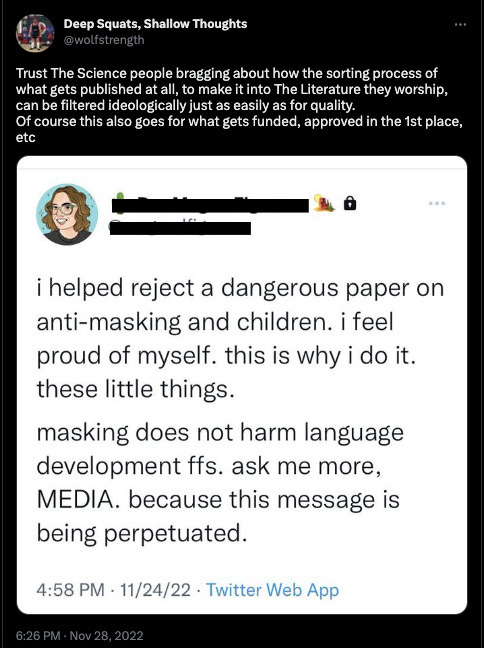

This is already very problematic, as surely you realized on your own. Our own eyes and minds can deceive us so easily. Surely we need modern methods and computers to stomp out these ancient, crude, simple devices ! Even worse, the peer review publication system hadn’t yet been set up. Hipparchus didn’t publish a single peer reviewed Randomized Controlled Trial during his entire lifetime, much less a double blinded one. Not even a single citation in his lifetime - not one!

The Solution

We must therefore reject all his findings as, at best, lucky guesses that the all knowing experts of peer reviewed journals would later discover for real, using actual science, not the primitive meanderings of old dead men. And we’re all a lot better for it.

The Lesson: Sometimes You Need to Believe Yer Lyin’ Eyes

Obviously the previous two sections were heavily laced with sarcasm. In posts on Twitter and Instagram over the last few years, I’ve made oblique references to my skepticism about the Evidence Based paradigm that seems, anecdotally, to be culturally dominant right now (see what I did there?), and which has made deep inroads into the way exercise science is studied in the lab, and is trickling down into the way it’s practiced in the gym.

Coming from a Biology major background, you’d think I’d be all for it. And indeed, after spending the first few years of my time in the gym getting info from Flex and Muscle & Fitness magazines, I then spent the first year or two of my professional practice as a personal trainer obsessively learning & implementing the evidence-based exercise guidelines from organizations such as the ACSM, ACE, and the NSCA. These guidelines didn’t encompass the entirety of my practice, but certainly a large part of it.

However, as the old saying goes, I didn’t become so open minded that my brain fell out. I trusted the evidence-based guidelines, but noticed that the results I was getting with my clients were, while not zero, relatively subpar. No one’s life was changed. Were their chances of coming down with some lifestyle-influenced disease reduced, on average, by 2.385%? Maybe. But that’s not really why people hire a trainer. They want large, impactful differences in how they look, feel, and perform. And as much as I didn’t want to admit it, I wasn’t giving that to them with all my science and evidence-based practices.

I delved into fitness experts and gurus - who would all be considered non-evidence-based by their lack of using primarily published literature as a guidepost - and learned something from almost all of them - Mike Boyle; JC Santana; Gray Cook and Lee Burton; Thomas Meyers; Pavel Tsatsouline and the entire RKC hardstyle Kettlebell school; CrossFit; Glenn Pendlay, Leo Totten, and Artie Dreschler and the traditional olympic lifting community and others - but still wasn’t satisfied. Results were better, their systems more in line with reality than the academic guidelines, but still didn’t have the impact on my clients’ lives that I was looking for.

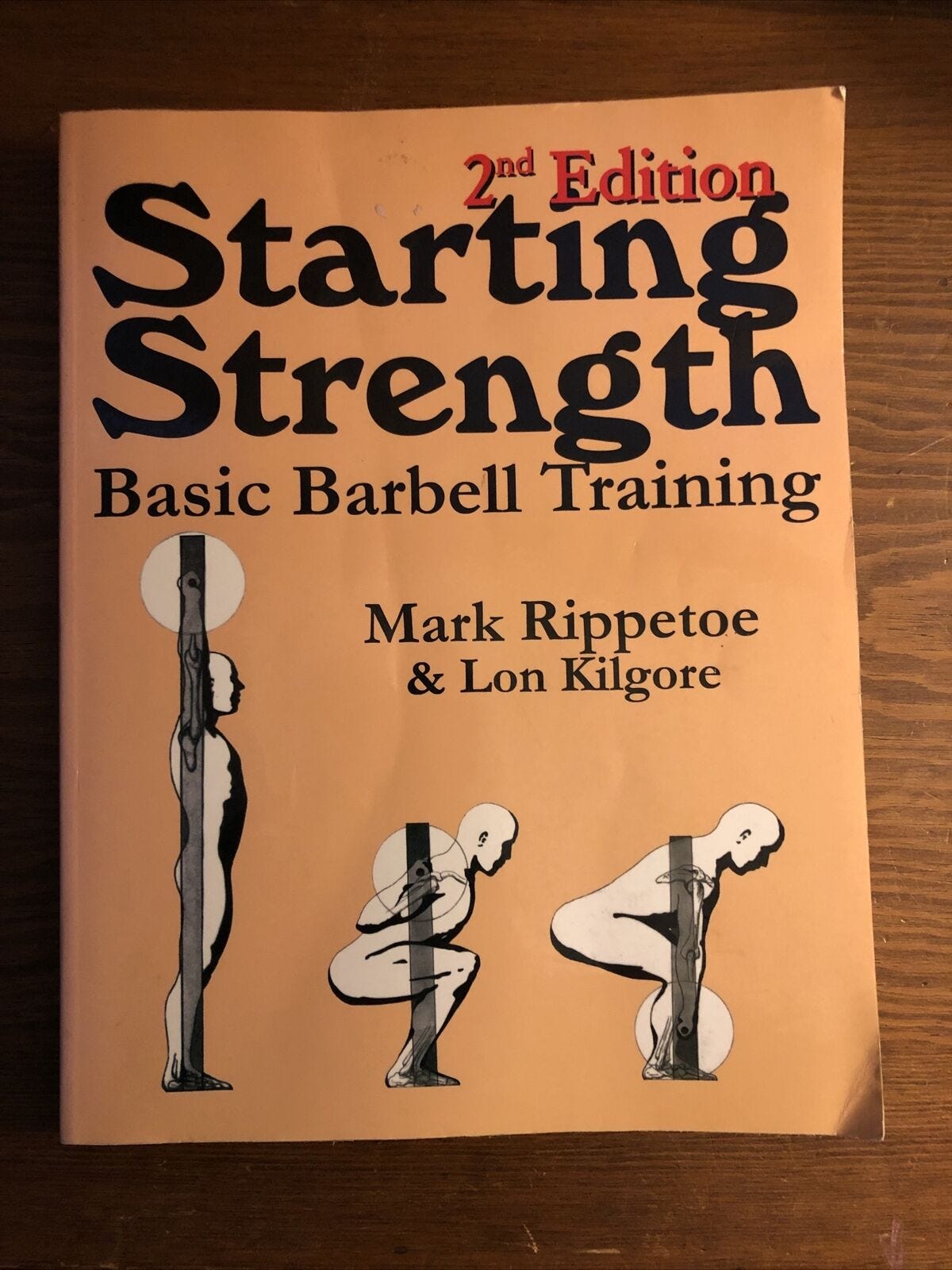

The major event that changed all that was when I discovered Mark Rippetoe’s Starting Strength 2nd edition in January of 2008. Now in it’s 3rd edition with significant updates, even the inferior 2nd edition was both more in line with the anatomy and physiology classes I’d taken as a Biology undergrad, but also - and most importantly - IT WORKED!

Implementing both the general principles and most of the specific instructions therein, I was able to give my clients a much more profound, impactful change in their physical and mental capacities, in a much shorter period of time, compared to both the evidence-based practices I had used my first year and the mishmash of other guru/expert based approaches I’d taken since.

While I don’t agree with every last line in the book nor everything else the author has ever written, the basic approach both made more sense, and worked overwhelmingly better in the field - in a consistent, repeatable fashion no less.

Interestingly, it had never been peer reviewed, and to this day, still hasn’t as far as I know. If I wanted to cite a “source” that the evidenced-based community would accept that doing a linear progression of 3x5 in the Squat, Bench, and Press, 1x5 in the deadlift, along with some chinups and possibly some power cleans, achieves incredible results, I wouldn’t have a great one. But I’ve successfully implemented it now around a thousand times myself, and altogether with colleagues I personally know, many tens of thousands of times

This doesn’t mean we don’t have a lot more to learn. I’d love to see what the outcome of a linear progression done via 4x4 or 3x6, instead of 3x5; the 12-24-36 month difference in outcomes between people who take the LP as far as humanly possible vs those who end it as soon as they achieve their first failure; the difference between those who start with chins right away vs those who do power cleans and only add chins towards the end. There are many interesting things we could learn, if the evidence-based field was more open to doing useful work.

But alas, right now, the chances of any and all of these propositions happening is less than the utility of the nearly useless ‘evidence-based’ guidelines I took so seriously my first year as a professional in the field.

You might object that sure, there is lots of useless garbage in the field, and that I should’ve scrutinized the evidence myself, rather than relying on institutions like the ACSM, NSCA, and ACE to tell me which evidence I should pay attention to. And you’d be right. I was both young and stupid - and time has only fixed the former. However even now, when I see some of what’s presented by the more sophisticated, updated, Sciency McSienceson enlightened ones in that space, I still sometimes see things that would make me have to not believe my own lyin’ eyes, which I refuse to do.

The longer I do this and the more people I coach, the more open I am to being wrong and changing my mind - at least that’s what I tell myself, I’m sure my own biases come into play sometimes too. But in addition to that, the less willing I am to accept evidence, no matter how supposedly authoritative, that requires me to accept that repeatable, consistent observations in the gym are solely a result of small sample sizes, placebo or nocebo, or bias.

I don’t have a perfect paradigm solution for how we know things in my field yet. And I don’t think that the published literature should be wholly ignored, either. But if someone tells me a study, or even a series of studies, contradicts what I’ve seen in the gym with my own eyes many times, I’m going to be skeptical of it, at least until real world efficacy can be repeatedly demonstrated across as wide a range of a people, demographics, and circumstances as I’ve seen for myself in my own practice.

Information based on this post from The Cultural Tutor

Along with his Wiki page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hipparchus

Hipparchus > Neil deGrasse Tyson

Starting Strength > 90% of the crap I've read on strength & conditioning.