Generally speaking I like bro science. While I’m not purely a bro scientist myself, I think more highly of it than I do the evidence-based approach, at least in the latter's current form. And while what I say here does not apply to all bro scientists, it does apply to some. Since I actually like bro science and want it to be better, I share stuff like this in hopes of making a small impact in that direction. Now onto the story.

I'm just about the most injury prone person I know. I get injured all the time, for seemingly no reason. It’s been happening to me since I was a kid, playing in little league and high school sports. No paradigm I've seen can explain it: not the classic biomechanical models, not the pain science and fatigue management models, nor does anything else I've ever seen fit the facts of my situation. My friend John Petrizzo is a practicing physical therapist and professor of exercise science at Adelphi University, in addition to being a strength coach and lifter himself, and he jokingly named my condition Wolf's Disease, because I'm so uniquely prone to it.

It's like I have a Ferrari engine but the suspension and chassis of a Yugo.

Sometimes haters try to use this as proof of either my own shortcomings as a coach, or the problems with my methodology. This is silly on its face, as I would have no business at all if even 10% of my clients had the same issues I do - thankfully, it's 0%. Likewise with friends or colleagues who use the same general approach - none have the injury tendencies that I have. Plus the fact that it’s been happening to me since I was a kid playing sports, not something that started only after I began training using my current methodology. It clearly has something to do with my own body, not my training methodology, as neither I nor the colleagues I’ve spoken to, have ever seen a single other example of it, in a sample size of tens of thousands.

So while it’s understandable why a very surface level analysis suggests something about my training or programming causes my oddly frequent tendency to get injured, even a slightly deeper look shows that surface level analysis to be incorrect.

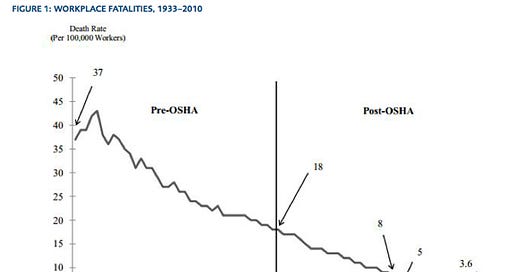

We can see a parallel to this by looking at OSHA, the federal bureaucracy created in the early 1970s, responsible for workplace safety. This is a graph of workplace fatalities starting from the founding of the occupational safety and health administration until ~40 years later.

The source for this data is the 2012 US Dept of Labor, bureau of statistics. As you can see, workplace fatalities started high and plummeted after OSHA was founded, thus proving that OSHA is effective and saves lives. We have a perfectly correlated graph and the obvious mechanistic explanation, right? Just like my training methodology and my tendency to get injured, right?

Wrong.

Here's the full graph, with data starting about 35 years earlier. What it shows is that workplace fatalities were already on a steep decline from a much higher point, and that OSHA's existence didn't even change the slope of the curve at all.

What we have here is the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. This translates to "after this, therefore because of this." It's pattern of reasoning that seems true but has a critical flaw, that occurs when someone assumes that one event caused another simply because the first event happened before the second.

In my case, the assumption is: something about my training style or programming caused the issue. I started training this way, then I started getting hurt. See, Wolf, your methodology caused the problem!

But if that were the case, my friend John - who is a practicing PT and has treated thousands and thousands of injured patients and coached hundreds and hundreds of lifters using the same basic methodology I use - wouldn't have jokingly named my problem "Wolf's Disease," because he'd see examples of it all the time. But he doesn’t, so it can’t be the training style or methodology.

If that were the case, the issue wouldn't have begun when I was a kid in little league, well before I ever picked up a barbell. In high school, I got injured playing sports more often than anyone else in my class or on any of my teams, despite being one of the better players. It got to the point that in high school, if I missed a day of class, my friends would all just assume I had a game the night before and got hurt. That's how often it happened.

If that were the case, my own clients would ditch me real quick, for getting hurt so often.

So, obviously, it is not the case that my training methodology is the cause of the problem. We don’t know what it is, but it can’t be that.

The OSHA chart provides a nice example of how this same issue can pop up in any discipline; it’s not exclusive to training or lifting, though it often manifests there. And how you can have a perfectly correlated chart, with collected data, and a probable mechanistic explanation. But it still doesn’t prove causation, if you are only looking at a small part of, rather than the whole picture.

Is the biggest or strongest guy that way because of his training style or in spite of it? With a sample size of one, or a small group (especially if they’re all very enhanced), we don’t really know. A peer reviewed RCT likely wouldn’t answer the Q either, because of the many flaws those studies tend to have, but we need a larger sample size to experiment and see in the real world.

This issue of the post hoc fallacy is one that some bro scientists recognize, and so are wise enough not to take one anecdote, even if confirmed as true, as the whole story. They're wise enough to look for repeating patterns in larger populations, rather than concluding with certainty from one example that may well be an outlier.

But many bro science bois are not so discerning. And they apply that lack of discernment to their whole approach to the gym: “Thing X worked for me, therefore it works in general.” Or, “Thing Y worked for CBum or Sam Sulek or Nick Walker - therefore it'll definitely work for me or everyone else, and anyone who even mildly suggests otherwise is an idiot.”

I'm not sure how common the wiser approach is vs the less discerning one, but I still see a lot of the less discerning one on IG and Twitter - not just among the rank and file bros, but among coaches as well. If we want to make bro science great again, we should try to encourage better critical thinking, even while avoiding the "citation desperately needed" meme-worthy attitude of the evidence based bois.

What the OSHA graph can't tell us is if improvement would have stalled without OSHA and / or have we changed our idea of a workplace injury and reporting them making the improvements even bigger.

One of my favorite twists on this idea is the BB mag origin stories where they'd use a prepubescent pic of someone like Dave Draper of Ahnahld as evidence that their gainz were able to overcome even their shitty genetics.