A Positive Vision For Expanding Our Understanding of Strength, Conditioning, and Fitness

Like science, strength coaching is a process, not an institution

Today’s topic will be strength training related, but we need to cover some background info about science in general first. Catching up on this prior article about how we know what we think we know about strength and fitness will be useful background for today’s article, but is not absolutely required.

Science vs The Science™

One of the most frustrating aspects of living through 2020-2022 was knowing how unscientific and even pseudoscientific the so-called science was, how much of it was an unprecedented experiment at scale with unwilling human subjects, yet still being subject to its tyrannies.

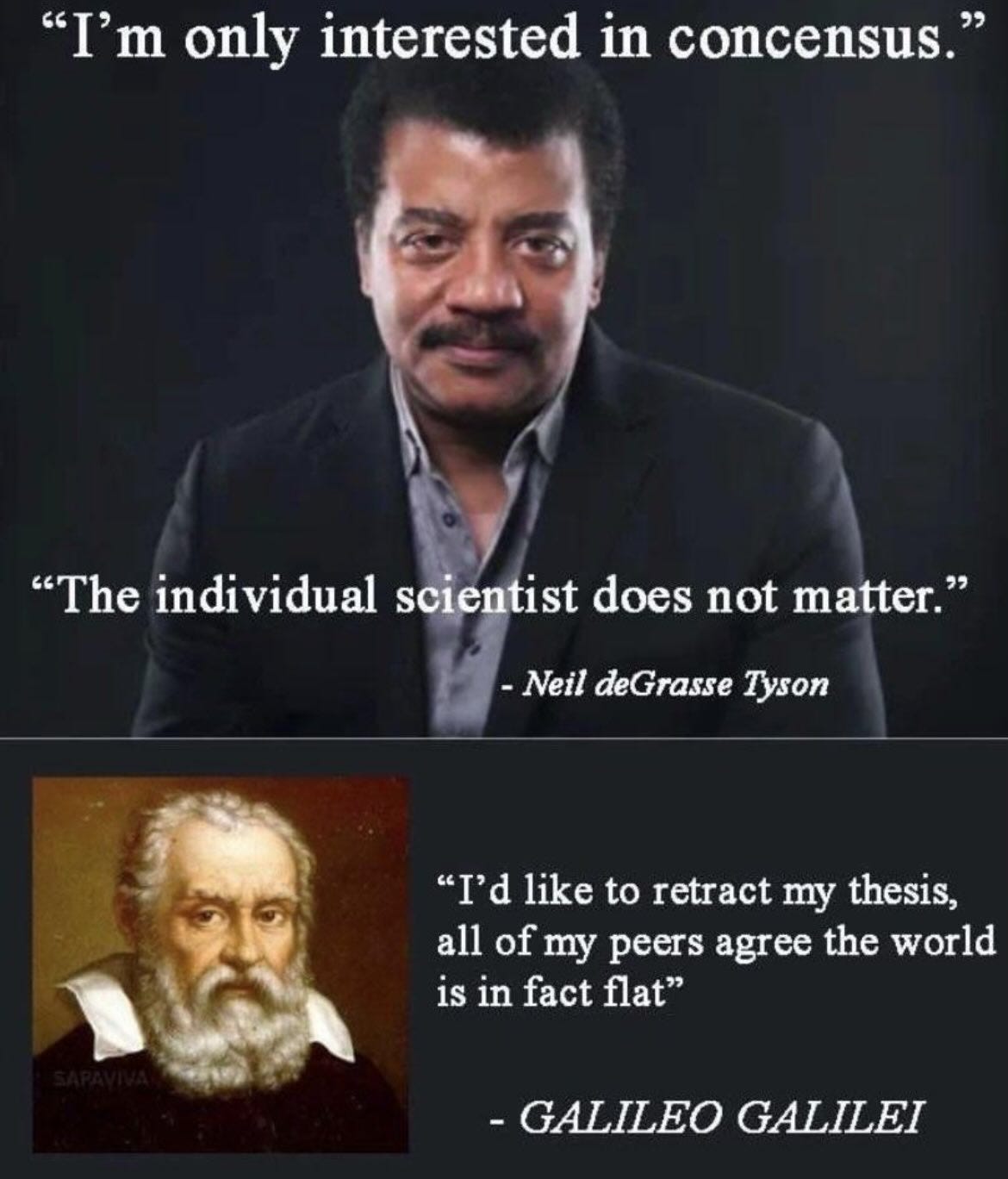

A small silver lining of that terrible time was the coalescing of a loosely organized resistance to the bureaucratic model of science that has come to dominate modern western society and governance. Even still today (for now), if you google “scientific method,” you will find no references to consensus or peer review in the top results. Yet those are the bedrocks of the modern managerial, bureaucratic conception of The Science™, as articulated by the most popular science communicator in the world, Neil DeGrasse Tyson:

It is illustrative that Tyson’s idea of science doesn’t reference the scientific method at all, only the consensus of The System. Not independent and consistently replicable outcomes and results produced by scientists who are wholly unrelated in funding, institution and institutional similarity, personal preference or investment in outcome, or personal belief and ideology. Not until the very end when he briefly responds to Bigtree’s insistence on the scientific method, does Tyson even mention it in passing, getting it wrong. The question at issue here isn’t the narrow one of who is correct on the topic they happen to be discussing. The question is a much broader one of which is the more scientific and correct approach to discovering truth. Whoever made this meme spelled “consensus” wrong, but the concept the meme points to, is spot on:

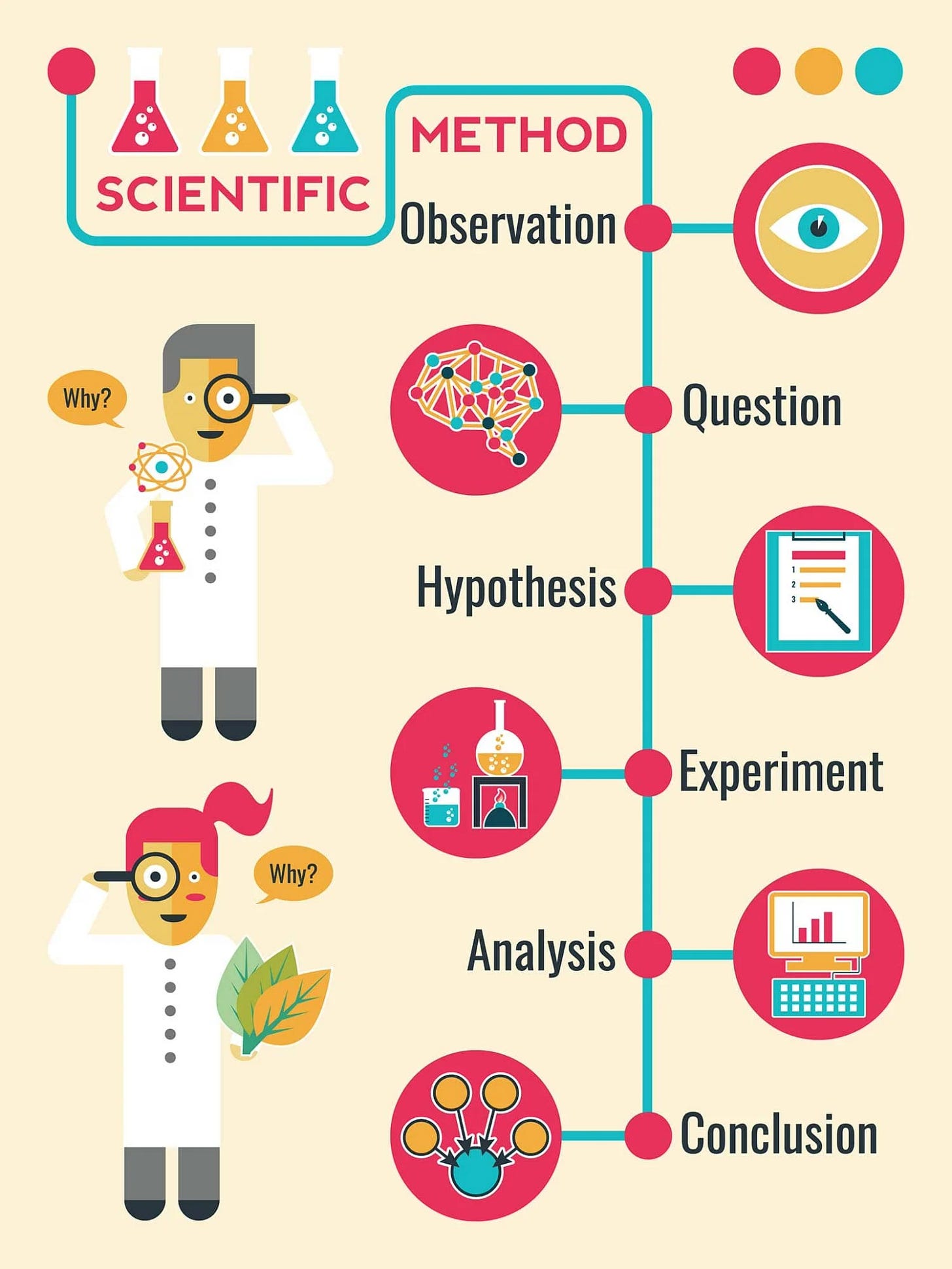

Where in the scientific method is consensus of the system, especially when that system excludes dissenters from having a seat at the table to present their views? I can’t find it, but maybe you can.

Here’s the current wikipedia version of the scientific method:

and here’s a couple other graphics from the top few search results on google:

It seems like everyone agrees that science and truth are independent of consensus and system, but at the same time, appeals to consensus and system trump every other scientific claim. How is this possible?

It’s a weird sort of cognitive dissonance wherein everyone knows that’s not what science is, but for a variety of reasons, anyone operating within the establishment paradigm pretends that it is. But those of us operating outside the establishment paradigm are free to say that The Emperor Has No Clothes. Science is a process, not a set of established facts. Science is a process, not an institution or a person. Science is a process, not a consensus. Science is a way of iteratively getting closer to the truth over time, not a gatekept cabal that only the right degree or white lab coat can get you invited into.

What Does this Have to do with Strength Training?

This managerial/bureaucratic conception of science also seems to be at the heart of the current evidence-based ideology, which implicitly (sometimes explicitly) holds that any claim not directly sourced to a peer reviewed citation is deeply inferior at best, and more often outright dismissible as a source of evidence.

I have written about and discussed problems and shortcomings with this approach many times. Show me a single strength training study that:

Controls for all the lifestyle variables like sleep, non-training activity, and nutritional intake; personal motivation to strive and drive hard during workouts and take sets to failure; past training experience in more than a vague way (“previously untrained,” “resistance trained males,” etc).

Has 250 subjects (still way too small to be a representative sample for generalizing purposes, but better than we get).

Is run for a full year or longer, allowing short term fluctuations to be ironed out, as well as giving a chance to see if something is a useful framework for training in general, or just something that works for a little while for a specific cohort.

Comes to a clear conclusion that doesn’t require extensive statistical legerdemain to claim an average outcome that really just means they’re covering for the fact that outcomes are actually individualized.

I don’t think you’ll find a single strength training study that meets these reasonable criteria, much less one that has been independently replicated multiple times, but I’d love to be wrong.

However, I don’t only want to be a Negative Nelly all the time. Granted this narrow evidence based approach is wrong, but what’s right? How SHOULD we approach this topic, then?

The two basic approaches taken in the field are:

What I described above as the evidence based approach

Some version of bro-science, copying what a successful athlete or lifter does or did, without analysis or understanding of any underlying model of why it works (or doesn’t), and hoping it replicates in general

In the links above, you can read about why I reject #1. What about #2? As I alluded to, without an underlying model or theory about how and why things work, you’re groping in the dark. How do you know that athlete wouldn’t have been even more successful with a different approach? How do you know that it wasn’t the athlete’s great genetics, work ethic, nutrition and lifestyle, possibly performance enhancing drugs - or a combination of those things - that led to his success, rather than the programming and training approach? You really don’t.

So while there is undeniably value in looking at the real world, not just what studies say, that value is also limited without more analysis, without some type of model to work with and measure things against.

We’ve established that strength and conditioning is too complex a system with too many unisolated variables to rely solely on either theory or studies on one hand, or copying what good lifters or athletes do on the other. Neither gives you a full understanding or picture of what works.

OK, cool story bro. How do we solve this?

A Positive Vision

The answer is not long or complicated, it doesn’t require a fancy degree or white lab coat to understand or implement, and isn’t laden with jargon that makes you feel superior for being part of the in-the-know, in-group. And unfortunately those things seem to have more appeal than the truth these days. But alas, forge on we must.

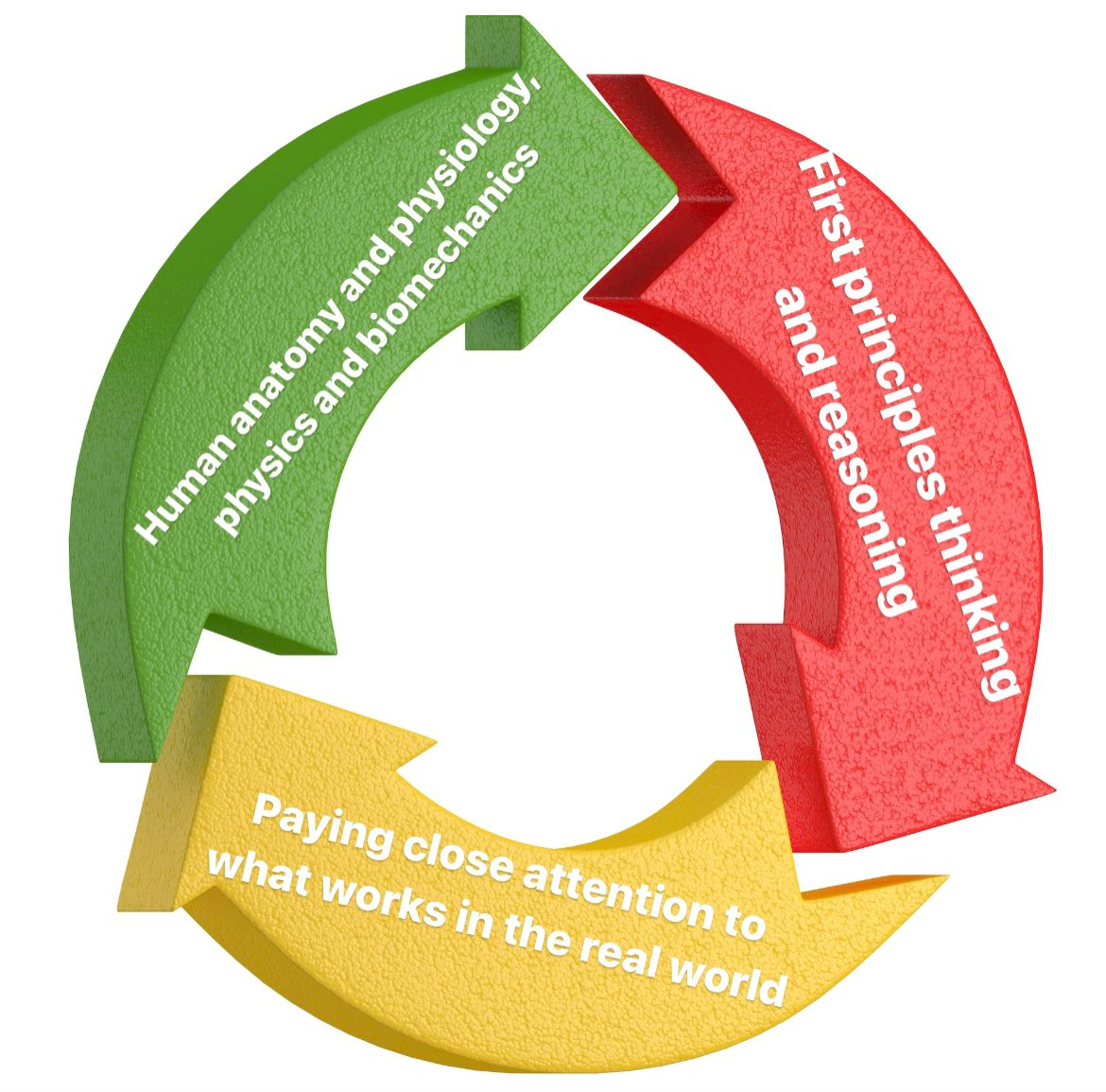

The solution is blending first-principles thinking with human anatomy and physiology, with physics and biomechanics to produce a model. Apply the model to training and coaching. Observe and see what works in the real world. How it matches your predictions, how it replicates for broad populations. Repeat. Iterate over and over again to refine.

“But,” I can already hear the Evidence Based Bois say, “that’s why we have studies - to isolate the variables and figure which thing made the difference; which cause led to the effect. Do you even understand science?”

My brother in iron, have you read any of the studies?!

My iterative approach seems superior to either the purely evidence based or bro science approaches. I’d also argue it’s truer to the scientific method than the “sola stud-tura” ideology that passes for evidence based today, wherein only peer reviewed citations from ✌🏻professional research✌🏻 as my friend Robert Santana (PhD, as it so happens) calls it.

It is this iterative approach upon which I based my article on the Linear Progression, which I’ve successfully coached many hundreds of people through, and on which all of them added a ton of weight to their lifts. It’s this iterative approach which led me to disagree with Rippetoe about the olympic press, even though his system is my primary influence. It’s this iterative approach, along with some good old fashioned disagreeableness, that led to my current ideas on strength and conditioning for athletes, which were praised and recommended by Stan Efferding, personal strength and conditioning coach for Jon Jones’ return at UFC 285.

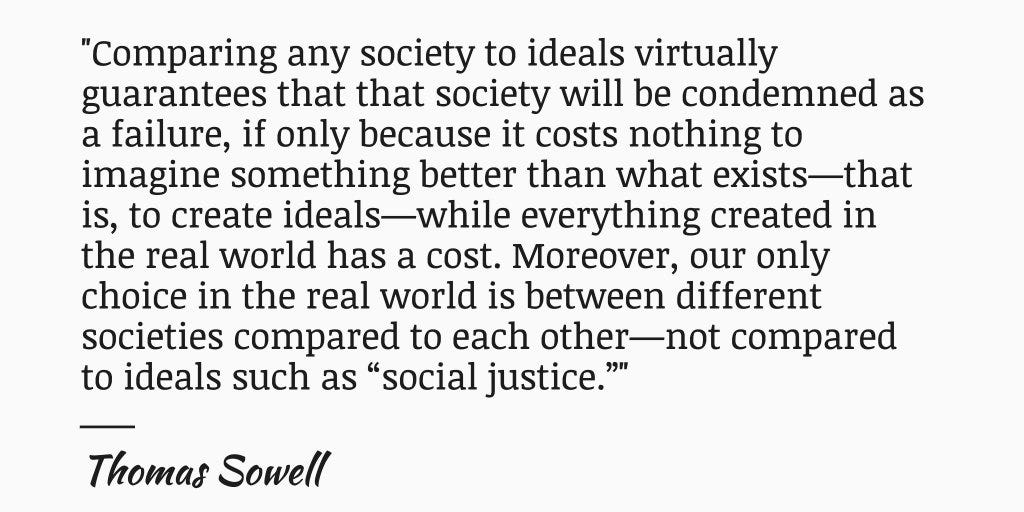

Is it a perfect approach? Of course not. But the question as always is: Compared to what? Compared to the imaginary perfect evidence-based paradigm that only exists in your head and helps you sell more templates, or compared to what it is in the real world?

Starting with evidence based hypotheses and the refining through hundreds of n = 1 iterations is a powerful method for applying a stimulus to a complex system. Strength and diet are two perfect examples, where you can perform countless mini-experiments in between the rare publication of good studies.