Though the evidence based bois and the bro science bois disagree about many things, some of them seem to come together in service of poo-pooing the importance of force production as a key element in strength training.

I generally get along with the bro science bois better because they’re less effete; more connected to what people are actually doing at the gym vs some weird protocol, dreamed up by a lab nerd to get government funding, and tailored for an IRB - none of whom have ever actually lifted - to approve; and not deferential to fake credentials and poor quality studies. But in this case, I have to say I disagree with both sides, who in this case agree with each other. First I’ll lay out their cases.

The Evidence Based Case

When it comes to the evidence based bois, a popular talking point is to minimize the importance of weight being lifted, when it comes to training. Their idea is that volume is the main driver of hypertrophy, as long as that volume of work is done above a minimum threshold of intensity relative to the lifter’s max, and reasonably close to failure. So, for example, if a lifter’s 1 rep max in a given lift is 300: his 5 rep max is estimated around 260 and his 10 rep max is estimated to be around 225, give or take. Given some leeway for fluctuations in daily performance, this line of thought says that 4 sets of 10 at 200-205 is better for hypertrophy than 3 sets of 5 at 250 or even than 5 sets of 5 at 240.

A good example of the ideas that back this up can be found HERE, along with a bunch of cited sources of studies and meta-analyses that suggest volume is more important than intensity - load - when it comes to hypertrophy, as long as a basic threshold is met for intensity.

This is further supported by citations of studies like van den Tillaar et al,1 which conclude that you get similar activation of the quadriceps muscles at single repetitions of the squat, at loads between 50% and 90% of a 1RM. Since almost no one trains above 90% with enough frequency or volume to drive major adaptations because it’s too exhausting, the idea is that as long as you’ve above 50% (some say a little higher but this study found 50%), there isn’t much difference as long as you get in the volume and do enough reps to be somewhat close to failure.

The Bro Science Case

I’m going to use a couple quotes here as examples for the bro case. They’re both from people whose content I enjoy, but disagree with regarding this one point, so am not going to cite or screenshot, just stick with analyzing the ideas.

Why You Can Do Any Rep Range You Want: Because they all work for building muscle and the idea that you need to follow an arbitrary cut off because so-and-so said so due to new rules made up by fitness "science and evidence" blowhards in the last 3 years is peak BS.

This appears to be in response to some within the evidence based community, contrary to the above, who are now saying you have to stick to specific rep ranges. A reply:

Needed to be said. These arbitrary rep counts are fucking stupid. Now I must do 100 rep hack squats today.

This echoes another theme I’ve seen recently in bro-science land, the 100-rep set:

This is the bro science case. The reps don’t really matter. Train insane at any rep range and you’ll grow. Now shut up and stop being a pussy. I agree with the attitude here, but not being a pussy with 5 reps is very different than with 100, and I’ll argue that this makes a big difference in the outcome of your efforts.

Why Force Production Matters

What both of these views miss is that rep range is intimately tied with force production, which is the most important and most foundational basis of strength and growth. To briefly recap, strength is the ability to produce force, which is the thing that causes movement.

Why does force production matter? It is the stuff of life itself, it’s how you interact with your environment from walking your dog to playing sports. It also determines how effective your training will be. At more advanced levels of specialization, maximizing for 1-rep force production is different than maximizing for muscular size, but they follow the same path early on in development before you’ve achieved higher levels of specialization.

This should come as no surprise, as it’s recognized in almost every other sport and discipline. Whether basketball, math or violin - we teach and develop novices differently than we do advanced players and practitioners, because we recognize the different needs of different people at different stages of development. Learn and master the fundamentals first, is the common denominator. This is true about training too, but for some reason is fought tooth and nail.

What does force production have to do with rep ranges? Pretty obviously, if you take a set to near failure at a lower rep range, you can use heavier weight than doing the same at a higher rep range. Heavier weight = more force. So a set of 100, 20, 10, 5 and 1, all of which are taken close to failure, will use very different weights - which means very different force production demands.

Radically different force production demands mean different training adaptations. If you can do something 100x before failure, by definition it's light. Not easy, but light. Think of a marathon - you do tens of thousands of steps before failure, but each step is in and of itself easy, doesn’t require much effort or force. It’s HARD, but only because of how many you do, not because any one step is demanding.

Contrast that to a 1 rep max squat. It’s hard in and of itself, not because of how many you do, fatigue from repeated bouts, or anything else. It’s inherently hard because of the force production demands of doing it even one time.

While sprinting isn’t exactly the same as 1RM squatting, they share the similarity that both are high force production/low rep events. And we can see the difference in (leg) musculature generated by sprinters and track cyclists on one hand, who do lower rep but higher force activity, and marathon runners on the other, who do high rep but low force activity. (Track cyclists are sprinters who compete in much shorter races on a dedicated track called a velodrome, as opposed to the longer races on actual roads of road cycling)

From left to right: track cyclist Robert Förstermann, sprinter Gail Devers, and Marathoner Ryan Hall - all elite athletes in their respective sports. The key question for us is: What kind of muscles and body does the combination of genetic predisposition, and a lifetime of dedicated training, for more vs less force production develop? It’s hard to look at that picture and say with a straight face that force production doesn’t matter.

And if force production matters, then the difference between a hard 5 rep set and a hard 100 rep set matters too, or even a hard 20 rep set. There will be large, even massive differences in the weight used - in the force production demanded - by these different events, and thus a difference in the outcome - just like we see in the pictures above.

Now it’s important not to get TOO bogged down by theory. In practice, it seems like people eventually benefit from work in different rep ranges, not just one rep goal all the time forever. But those are relatively small differences between, say, 5 and 10 rep sets, which won’t use monumentally different loads. But before we get into those details and weeds, we need to establish the basic premise: force production matters. A lot. And that means rep range matters too.

Even the difference between someone like Devers who competed in events of 60-100 meters - all out sprints requiring max force production for low reps - is quite different than those of 800 meter runners. 800m is A LOT closer to 100m than a marathon, and yet the difference is still stark. Here’s what the leaders of a recent D1 800 meter championships look like:

Fit, certainly, but a lot thinner and less muscular than their 100m counterparts:

And this is only the difference in force production between two (relatively) high force production events: 800 vs 100 meters. This tells us that even among two relatively higher intensity events, more intensity still matters.

Exactly how this carries over to lifting when it comes to sets and reps is up for discussion, I almost never go above 15 reps myself, but the broader concept is readily visible to the naked eye, and logically understandable to anyone who can tune out appeals to complexity in favor of straightforward evidence and basic logic.

The claim is not that absolutely maximizing 1-rep force production above all else, forever, produces the biggest muscles and most growth. But the claim is that 1) force production matters, a lot, and it needs to be high, and 2) even among different relatively high force production demands, hand waving as “as long as it meets a minimum threshold, it doesn’t matter much,” doesn’t seem to hold in the real world as well as it does in studies. Likewise, doing 100 rep sets even with all the mental toughness in the world, isn’t going to have the same effect as a few heavy sets of 5, due to the impossibility of doing 100 reps with anything approaching a high force production demand.

In other words, both the evidence based and the bro science bois are missing part of the picture.

Science

While not dispositive on its own, this is all in line with what we’d expect to see based on the concept in neuromuscular physiology known as Henneman's size principle. Also known as the size principle, it states that motor units are recruited in order of size from smallest to largest, depending on the intensity of force being applied. This principle describes the relationship between the properties of motor neurons and the muscle fibers they control, which together are called motor units. Motor neurons with small cell bodies tend to innervate slow-twitch, low-force, fatigue-resistant muscle fibers; while motor neurons with large cell bodies tend to innervate fast-twitch, high-force, less fatigue-resistant muscle fibers. As contraction increases, smaller motor units are recruited before larger ones, resulting in a smooth increase in muscle strength.

While we must always be on the lookout for evidence that calls established science into question, Henneman’s size principle strongly suggests that you need to produce large amounts of force to recruit the higher and highest threshold motor units, and thus train the muscles to their full potential. And there would be differences in strength and muscle size development between doing most of your work in the 50-55% range per van den Tillaar vs prioritizing the 80-85% range, for example.

In Practice

Does this mean everyone should just work on their 1RM squat, bench, and deadlift all the time and that’s it? Of course not. The concept and theory elucidated above leaves plenty of room for variance in exact implementation. For more advanced lifters who have already developed a solid base, there is a place for higher rep work than only doing sets of 1-5 reps or 1-8 reps; there’s a place for regional hypertrophy work; there’s a place for isolating muscles instead of doing only compound lifts. This is borne out empirically by what we see time after time in real life, whether bodybuilders, jacked powerlifters, or just gym enthusiasts who are jacked.

In 1957, Dr. Elwood Henneman discovered the size principle which states that motor units are recruited in order from smallest to largest depending on the intensity of the force being applied. This principle is important in regards to strength, hypertrophy, and rate of force development. Maximum recruitment of high threshold motor units is necessary for either of those three adaptations to take place. However, I have shown that there are differences required to maximize each adaptation.

Maximum Strength requires maximum effort, maximum velocity for a particular load and exercise, and very high loads for improved absolute strength…

Maximum hypertrophy requires maximum effort, maximum velocity for a particular load, velocity loss of 40-50% regardless of initial load, and a final velocity near the exercise’s maximum velocity threshold.

Maximum improvements in the rate of force development require maximum effort, maximum velocity for a particular load, and a substantial amount of time and volume spent at a particular velocity zone.

As always, the proof is in the details. This is why almost all coaches that teach the basics correctly will still get results.

My point here is not that maximum force production and nothing else remains the sole deciding variable for every possible fitness outcome and goal for the entire life of your training career. The point is that force production is highly important, that you can’t just work hard at whatever rep range you want and achieve the same results, and that this is all fairly expected and predictable from basic concepts in muscle physiology. While advanced training for already developed athletes and lifters can vary, advising beginners not to get stronger is doing them a huge disservice.

So you need to be driving intensity - weight on the bar - as a major part of your progressive overload scheme, for a low enough number of reps such that force production is actually trained and challenged.

The more of a beginner you are, the more important this is because the stronger you are, the more room you have to play with productive reps. For example, if your 1RM is 500, you can use a lot more weight - in other words do a lot more force production - for 8, 10, or 12 reps, than you can if your 1RM is 225. This is why a Novice Linear Progression is recommended for everyone starting out, whether your ultimate goal is to be generally fit, to powerlift, or to bodybuild. Building a base of hypertrophy and strength simultaneously and efficiently, which the Novice LP does, sets you up to be in a great position for any future fitness goal or endeavor, and this roughly explains why.

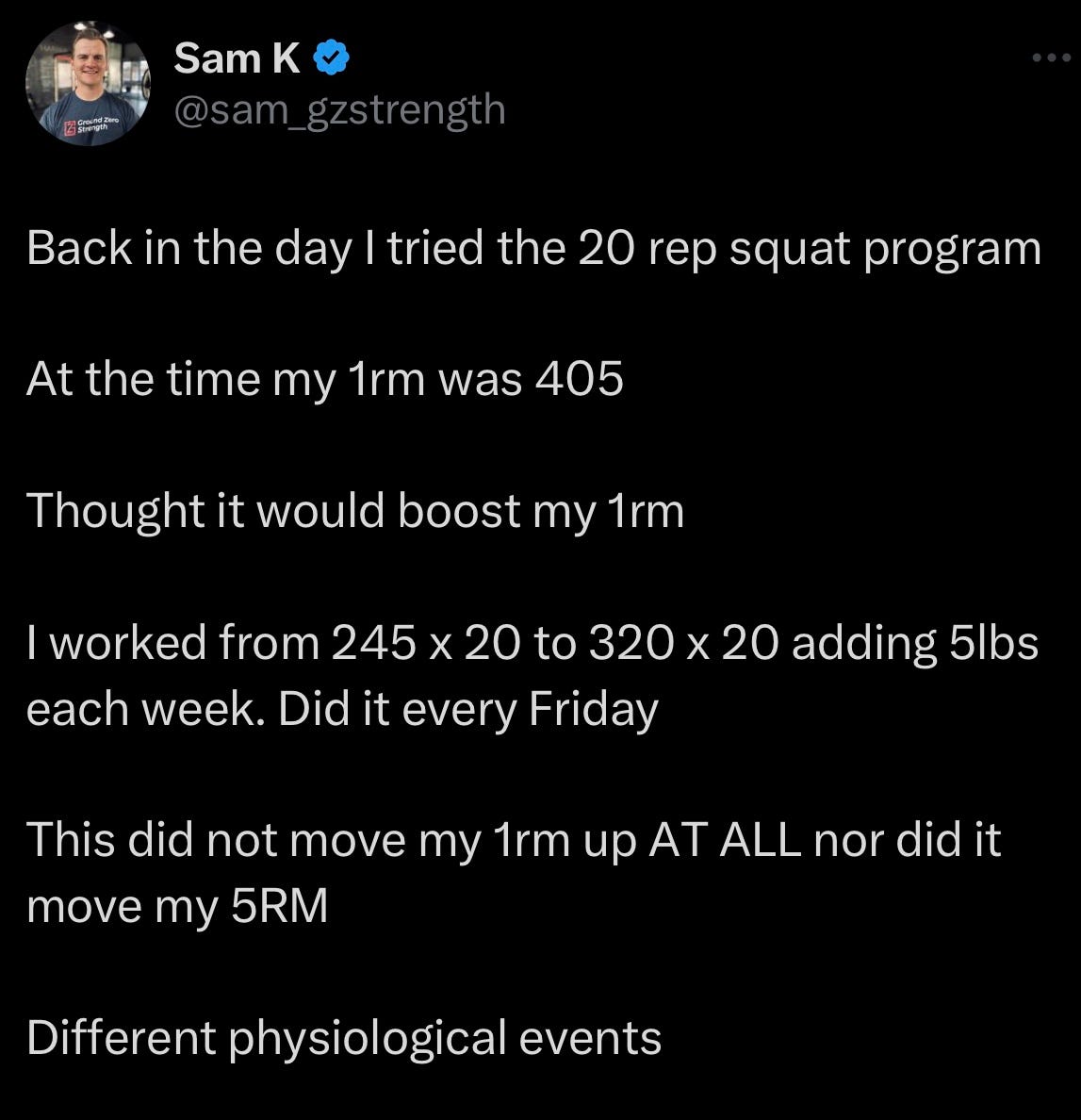

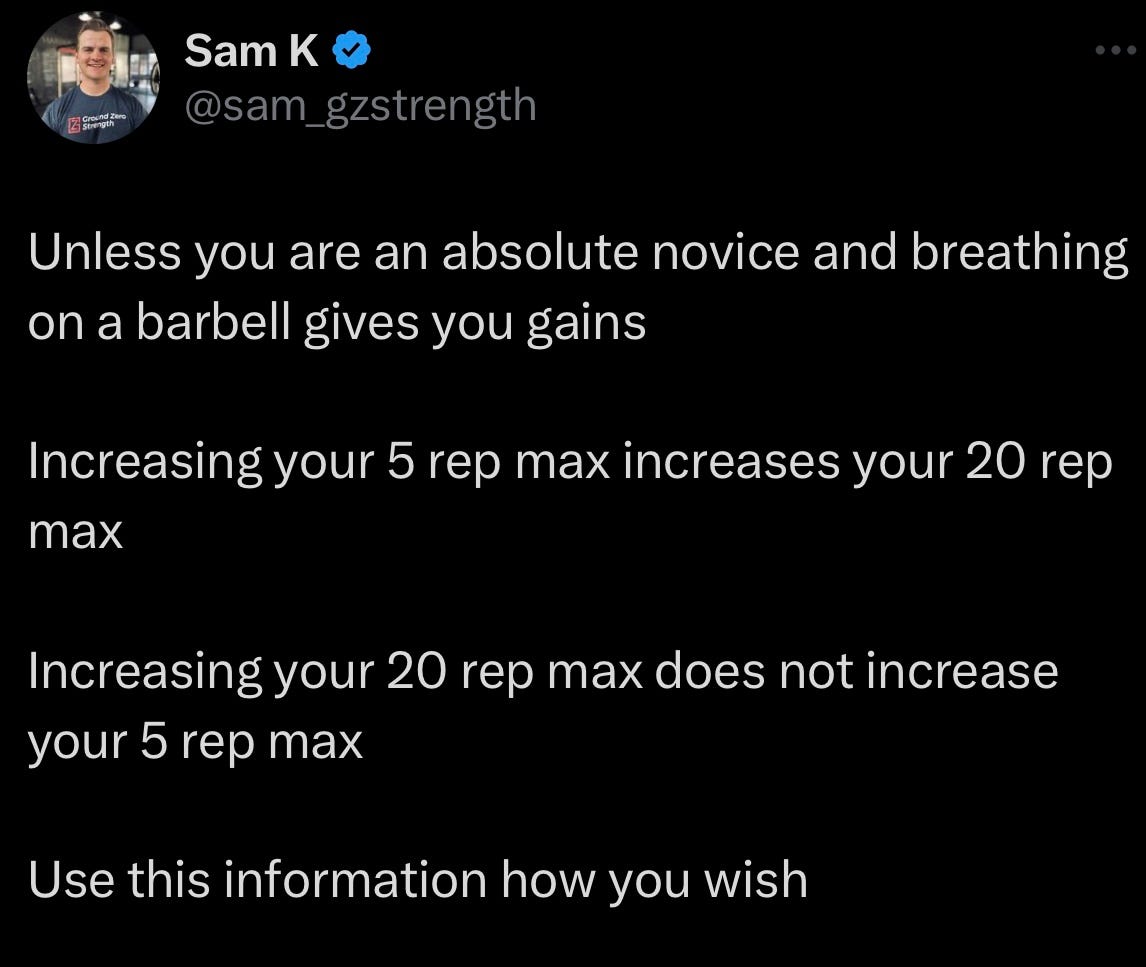

And look, I’m not even saying no one should EVER do a 100 rep challenge or anything for any reason. But the words of Sam Krapf of Ground Zero Strength are illustrative here, and representative of what I’ve seen in practice, just about every time:

Aside from today’s article, I broke down some reasons I don’t find the the van den tillaar study to be a convincing argument against weight on the bar in this piece , and the volume meta analyses in this piece

I can't believe people are honestly espousing 100 rep sets. How long before that becomes 200? 500? 1000? Where does this madness end?

Good article Wolf. I say work in a rep range you find sustainable and enjoy for the most part. For me that’s doubles and triples up to 8’s. If you enjoy high rep work, go for it, but I think it sucks. I’m going to do my faves now….because anything above 8 is cardio in my world😜😛.