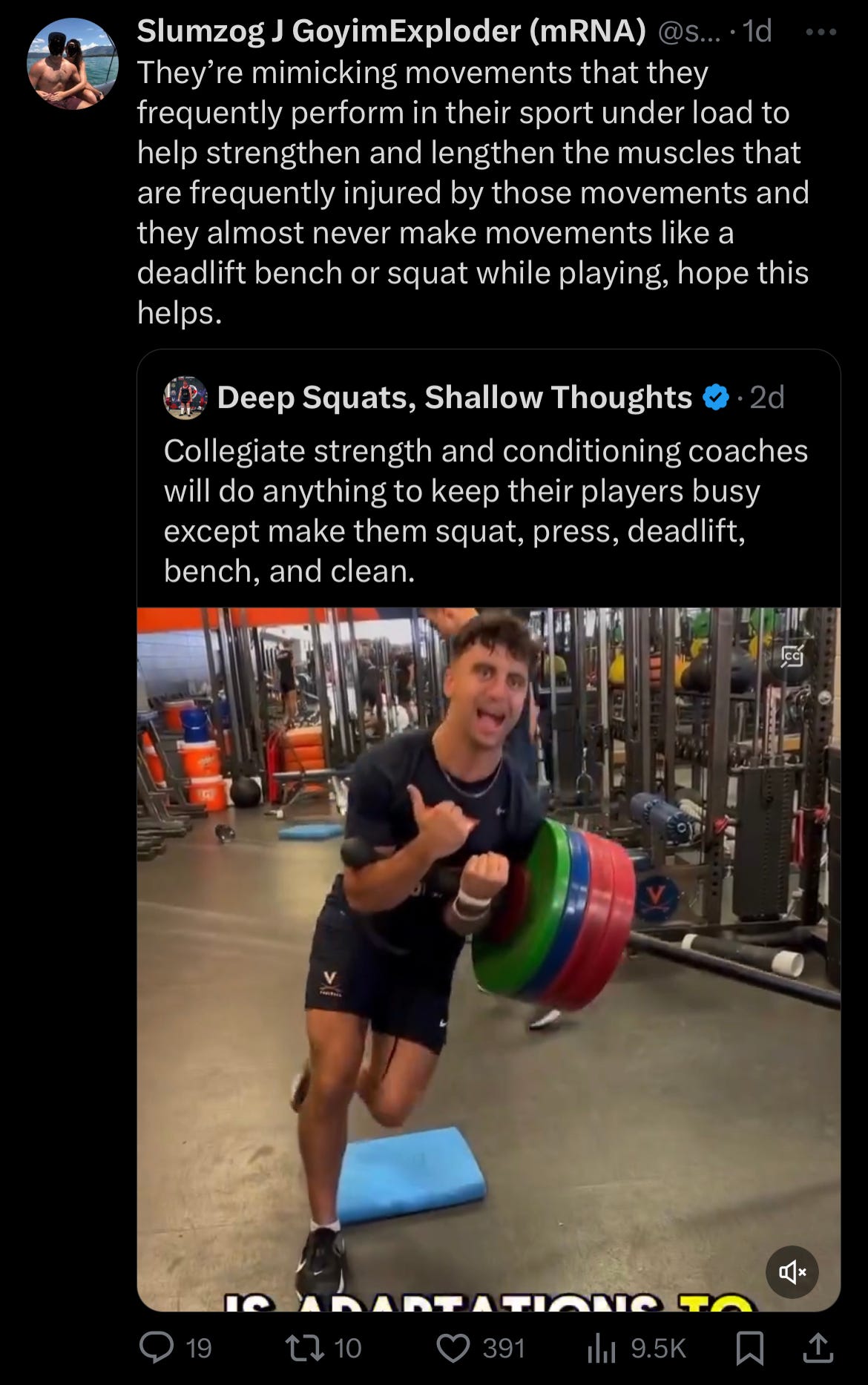

I created a bit of a kerfuffle on twitter this past weekend with this post, which was quasi-tongue-in-cheek commentary on the standard practices and worldview within the strength and conditioning industry. As of now, the post has over 203,000 views and a corresponding number of comments, many of which are very upset.

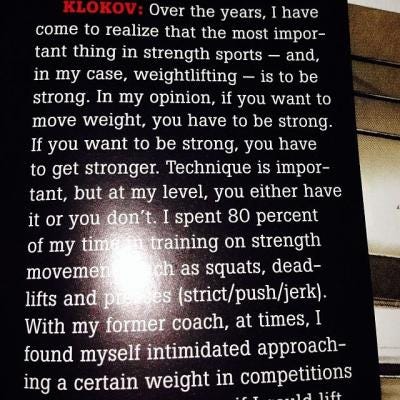

Though it was not a 100% serious post, it does reflect the schism between the minority position, which I share - that basic, general strength is paramount and comes first, and the majority position, which is that all sorts of sport specific, position specific, ROM specific, vector specific, and every other type of specific training imaginable should be emphasized.

I always reiterate here that when it comes to this topic, I am not an absolutist against any and all sport-specific considerations. What I do think is that:

General strength improvements have a great deal of carryover to any endeavor, athletic or otherwise, thus:

If not already strong, getting strong is the lowest hanging fruit, the easiest way to get the most bang for your buck on training, and therefore:

Until an athlete is already strong, nothing more than basic strength need be developed in the gym, primarily using basic barbell lifts (squat, press, deadlift, bench press, clean, and maybe snatch) done in a way that optimizes strength increases. During this time, all sport-specific concerns are best developed via practice on the court or field.

I’ve also written about this topic before here, here, and here - good background info if you haven’t read them yet.

Once an athlete is already strong, the details of which depend on the sport and position - a basketball point guard obviously need not be as strong as a football offensive lineman - then there is room for ‘filling in the gaps’ and optimizing with some sport specific considerations. This should not replace basic strength training, but can be added as a supplement to it, in reasonable doses, and in such a way as to be complimentary to, and not interfere with, the continued basic strength and power development that will still be beneficial.

Barbell Lifts Do Not Equal Powerlifting

One thing many of the angry comments on that post told me is that there is still a lot of fundamental misunderstanding of why athletes train in the gym at all, and how training works. Just like driving a car to the grocery store does not make you a race car driver, so too performing the squat, bench press, and deadlift does not make you a powerlifter.

The sport of powerlifting includes squat, bench, and deadlift. But the concept of powerlifting is Force= Mass x Acceleration. We use this concept for athletes, we don’t use the sport. Training for general strength is optimizing force production, which is the basis for all athletic development, as I have already written about at length. Whereas the sport of powerlifting involves maximizing the weight you can lift within the confines of the rules of the sport, which isn’t the same thing as optimizing general strength via force production.

The easiest way to imagine this is to think of a normal bench press with a small to moderate arch and moderate grip. This optimizes upper body force production development. To illustrate, here’s an example of me bench pressing 465 with a small arch and moderate grip. The idea is to move a heavy weight through a long effective ROM, in order to get a general strength training effect:

Now contrast this with the type of bench press we often see in powerlifting: a maximum width grip to go along with a maximum arch, not in order to develop maximum force production or general strength, but to maximize the weight lifted within the confines of the rules of the sport:

Clearly there is a massive difference here between strength training on the one hand, and powerlifting on the other, yet many people simply associate doing some of the barbell lifts with “powerlifting,” the same way some uniformed people associate cleans and snatches with “crossfit.”

One of the other tells of the simplistic character of this critique, is that I included the (overhead) press and the clean in my tweet, and there are approximately 0 serious powerlifters in the world who train the press and the clean with equal emphasis as they train the squat, bench, and deadlift. The press and the clean are excellent for general strength and power development, but are not trained as primary 1st-tier lifts by almost any powerlifters on the planet. Yet the peanut gallery still chimes in with derogatory comments about athletes not being powerlifters.

While this type of low-IQ idiocy is probably impossible to stamp out completely, I suspect a lot of people who reflexively hold this position can be reasoned out of it, given a compelling argument and analysis. Hopefully I have now provided that, so that you can tell the difference.

As I said earlier in this section: The sport of powerlifting includes squat, bench, and deadlift. But the concept behind powerlifting is Force= Mass x Acceleration. We use the concept for athletes, we don’t use the sport.

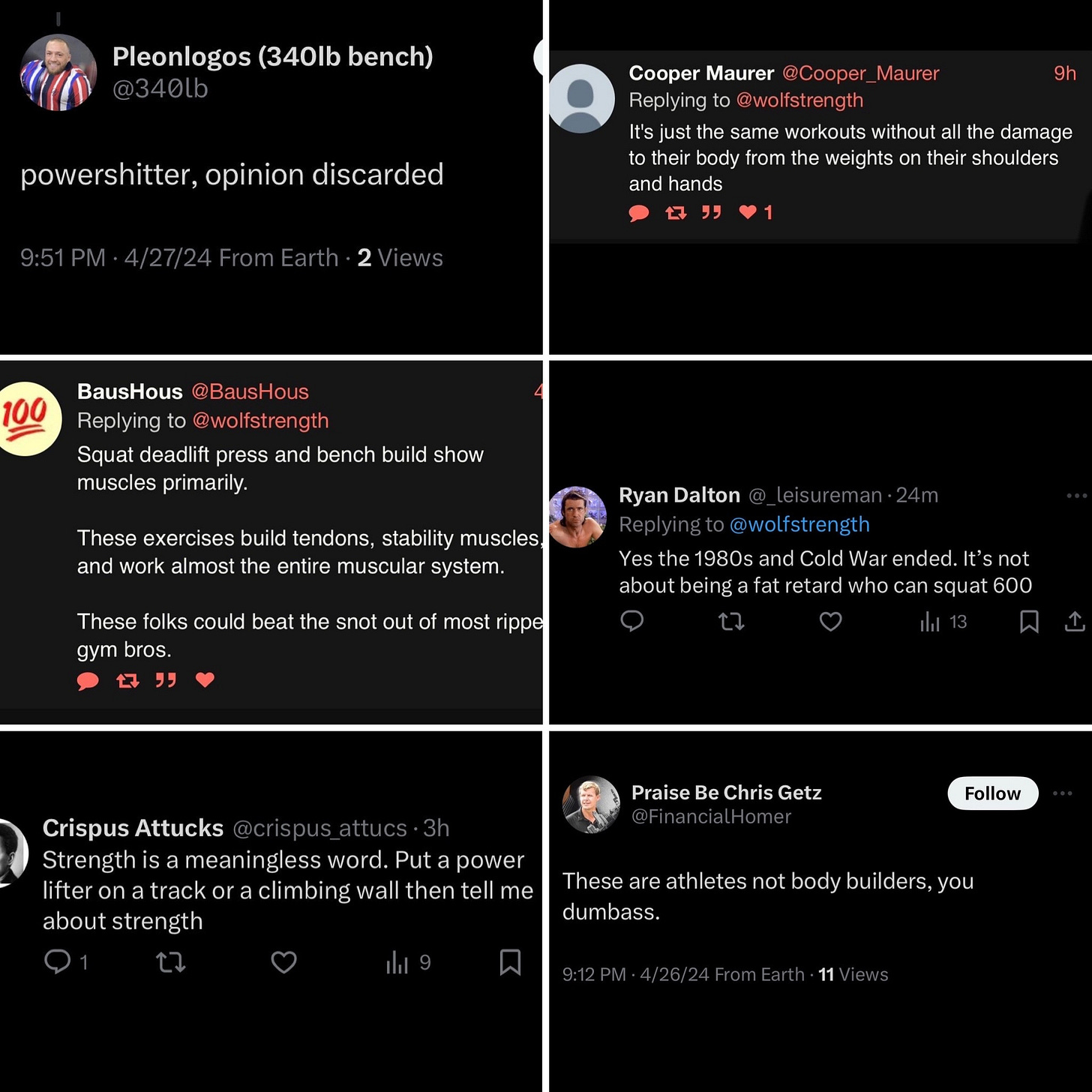

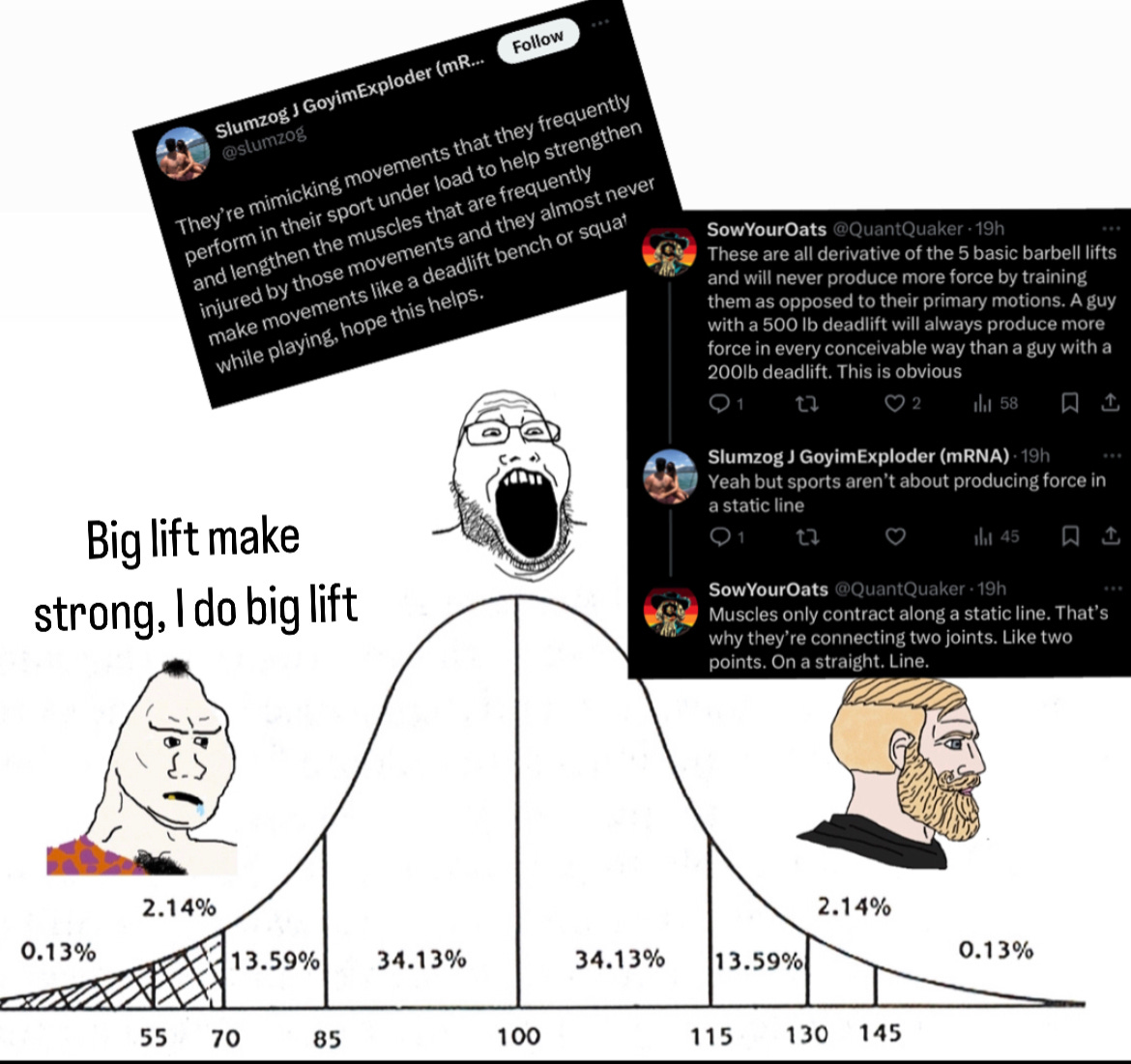

The most paradigmatic and stereotypical critique along the powerlifting lines was as follows:

In other words: Smart people, unlike dumb powerlifters, know that athletic training requires the movements to look like, and mimic, the movements the players do on the field and court, but loaded with weight. This brilliance, unlike your dumb old-fashioned linear lifts that don’t replicate any on-field movement, is the essence of enlightened athletic training!

LOL LMAO even. The bell curve meme was practically invented for such a scenario. As was already pointed out in the comments there, which the rest of this article is an elaboration of:

Why Lifts in the Gym Do NOT Need to Mimic or Look Like Field or Court Movements

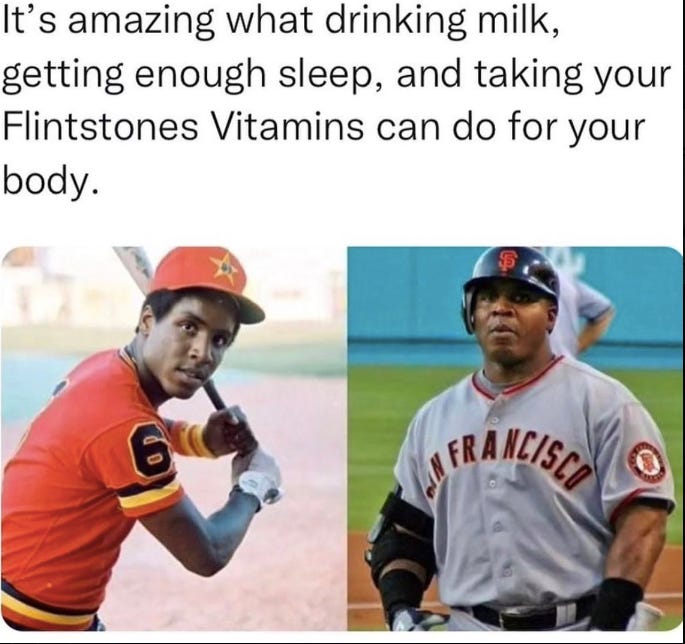

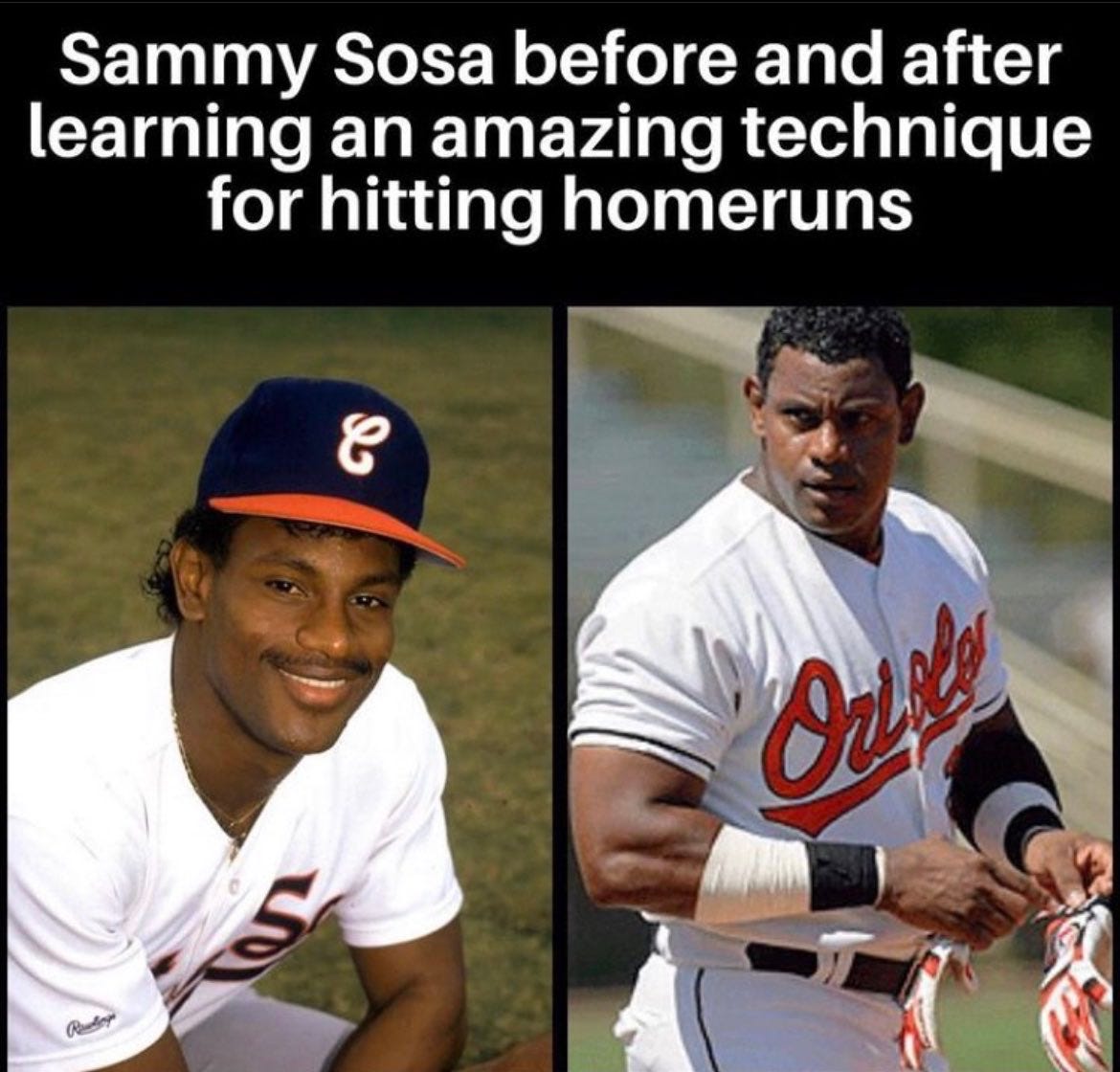

The main reason athletes go to the gym is to get stronger, to increase their force production capabilities in general. That’s why so many baseball players in the 90s and early 2000s took steroids. There are no technique steroids. There are no “batting eye” steroids. Steroids don’t improve any position specific, vector specific, or ROM specific strength or power. They help make the ballplayers generally stronger and more muscular, and with that advantage, the players then slugged an unprecedented number of home runs.

I have never seen a compelling response to this from the sport-specific position. Sure these players (allegedly) used PEDs to help them, but the point is what the result was: stronger, more muscular players in general, which resulted in immense sporting success. Using the squat, press, deadlift, bench, and clean accomplishes the same thing: making you stronger and more powerful in general. We want to achieve that physiological effect of general strength improvement in the most efficient and effective way possible, which is by doing the aforementioned barbell lifts. We don’t care so much if other people achieved the same result in an inefficient or illegal manner, because we can do it effectively with barbells.

Lifting in the gym, at least the general kind of strength building with barbells that I’ve been discussing here, does not and indeed SHOULD NOT aim to mimic the target activity on the court or field: Doing so requires use of loads that are too light to be effective for strength training, but without the benefit of practicing any of the necessary delicate and precise skills in the way they’re used in a game or event.

This is why we don’t have football linemen “squat” using their stance they take on the line. We have them squat in the way that best facilitates general force production. The idea that the general strength work has to mimic the exact positions of the sport is incorrect. It’s supposed to get you generally stronger, better at force production.

Once you are already very strong, perhaps there is some place for then filling in the corners with some sport-specific stuff, but until then, it would be like trying to solve poverty by giving pennies to the homeless, which is of course useless. However, giving pennies IS useful to someone who has the $47 to pay for the thing, but is just missing the $0.03.

You still don’t make the movement look like the field movement, but you might, for example, add some deeper high bar or front squatting to train additional ROM under load, do rotational or anti-rotational work, or some intelligently designed single leg work. None of this involves attempting to mimic field or court positions, but creates generally useful physical adaptations that are more specific to a particular sport’s needs than only doing the Big 6 barbell lifts, chins, and rows.

The Controversial Olympic Lifting Implications

The analysis above suggests that low bar squats done to below parallel with a moderate stance, toes out and knees out to match, might be better than high bar squats for the purpose of building general strength in olympic lifters, too. They must obviously still train and practice the technique and positions of the actual sport - cleans, front squats, jerks, snatches, etc. And then once their general strength is already well developed and strong - keep in mind this is a very strength dependent sport - there’s room for variations to bring up weak points or areas and keep it fun, which is where high bar squats can come back in.

The only squats that are truly specific to a sporting event or skill here are the front and overhead squats for olympic lifting. And indeed olympic lifters should front squat. But high bar squats are not specific to any sport, be it olympic lifting or otherwise, so whether for olympic lifting or any other sport, squatting is done for general strength purposes. If so, doing it in the way that best builds general strength makes the most sense, at least until you are already very strong.

Once strong, such things as proportionality, some muscles/movement patterns being more important for a given sport, and variety to keep it fresh, come into play. But high bar squats are trained for general strength preparation, not a specific sport movement, and thus the normal ideas of general strength preparation should apply.

All descriptions of high bar squats as “more athletic” that I’ve ever seen, are either merely the speaker’s subjective aesthetic preference, or else based on the mistaken notion discussed above that the general strength preparation lifts in the gym are supposed to “look more like” the target activity on the field or court, as opposed to be optimized for increases in general force production.

Some Counterarguments

What I usually hear in response to this idea is that the proof is in the pudding: no high level olympic lifters do it this way. While not 100% correct - I coached my friend Nick at the 2013 American Open and he only did low bar and front squats in his training leading up to it, and went on to clean and jerk 405 lbs in training a couple years later - it’s true as far as I know that no actual olympic-level lifters do this. But the same thing was equally true about all the best high jumpers in history prior to Dick Fosbury proving them wrong. In our case of olympic lifting, it’s not that hundreds of high level lifters have given this idea a real honest try, getting proper instruction and trying it for a couple years, and then failing at scale. It’s that they mock you for even suggesting it, and won’t try it. Of course it would have to be tested on many high level lifters to have a better idea if the theory works in practice, but the theory is pretty sound and my experience is that it’s worked out exactly the way I’ve described for all the hundreds of crossfitters I’ve coached who also did the olympic lifts regularly. I would bet on it, given a chance.

Here’s Nick’s 405 clean and jerk, just because it’s cool:

Likewise the counter argument for S&C is usually well who do you think YOU are to know better than the best strength coaches in the country coaching the best athletes? This is somewhat laughable, as the recruiter does the job of selecting for elite genetics in the athletes. You can give freak athletes just about anything, and being the freak athletes that they are, will make you look a brilliant coach. This reminds me of the people who, during covid, said we weren’t allowed to question doctors or epidemiologists who were saying things that were obviously wrong, and which required no specialized expertise to disprove them - just basic familiarity with publicly available statistics and reality, compared to what the doctors had said beforehand. Likewise, some of the worst strength coaches in the world populate D1 and pro teams payrolls, and appealing to their authority is a poor argument.

But if you do decide that appeal to authority is for you, remember not to forget your knee pads when rushing to defend the experts.

So how do you tease out the cause and effect? How do we know if the S&C coaches who de-emphasize strength in favor of lower force production capacity but mimicking the field positions and vectors with lighter weights, are correct or not?

Well my analysis aside, you find a football player who is kind of out of shape but is just huge and brutally generally strong, and watch as he tosses the other D1 players around like rag dolls. Then you understand the utility of general strength.

Steroids really should be enough to cinch this argument. But if covid has taught me anything, it's that people love to fight against the obvious.